This post was originally published on this site

Walking into the Museum of Pop Culture’s latest exhibition, Never Turn Back: Echoes of African American Music, you’re met with sound—intentional and stirring. The rhythmic creaking wood conjures a slave ship crossing the Atlantic. In the distance, the wailing of Sam Cooke’s “A Change Is Gonna Come” rings out promisingly through the space. It’s clear from the outset that the exhibition is a tribute and a sermon.

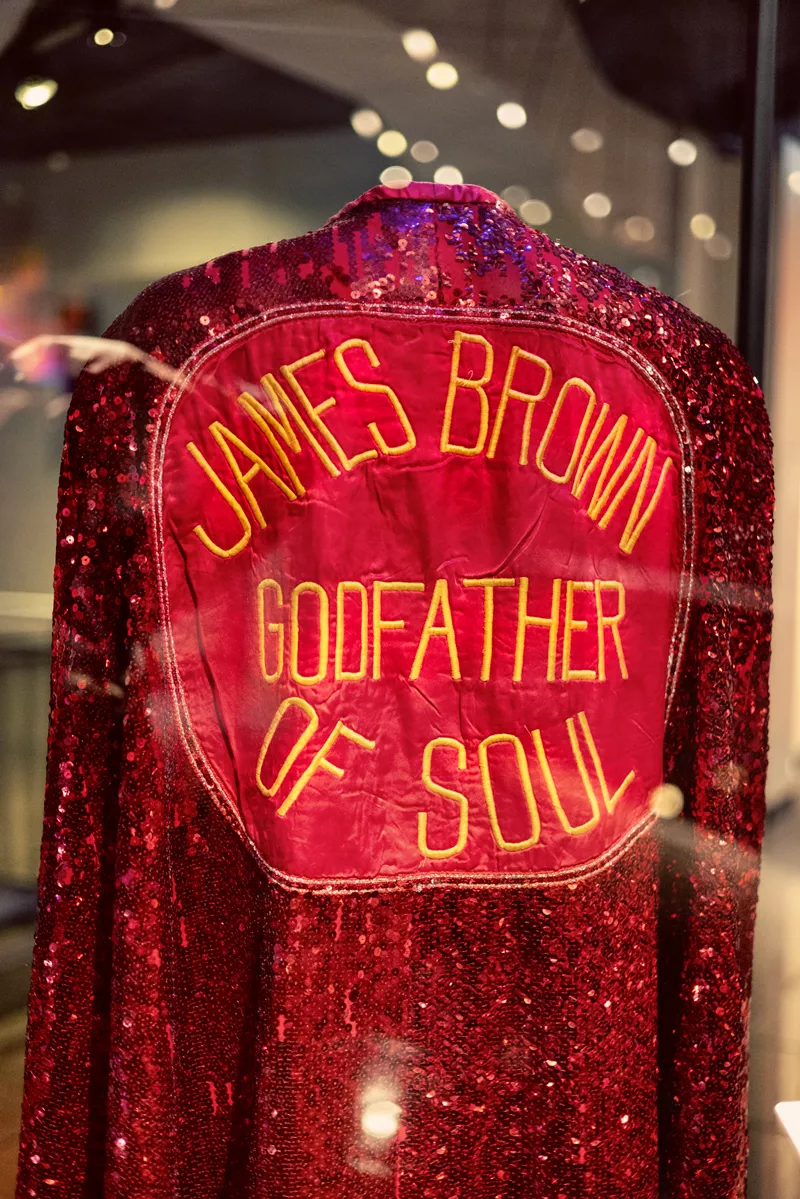

Never Turn Back marks a milestone for the museum: a framing of American history through the lens of Black music, curated by MoPOP’s first-ever Black curator, Adeerya Johnson. The exhibition traces a lineage beginning from Negro spirituals and gospel to jazz, blues, soul, and hip-hop—genres born out of the Black experience, shaped by oppression, and wielded as tools of jubilation and protest.

Johnson’s vision for the exhibition is inseparable from her own background. A Decatur, Georgia, native and PhD student who coined the term “Dirty South Feminism,” she speaks of the Black South with a clear sense of its cultural power. “I am a Black girl from the South. I love to say that. Within the past five years [living between Vancouver and Seattle], I’ve leaned into the idea of the privilege of existing in the Black South,” she says, noting the advantage of being immersed in communities that reflect your cultural identity, from your neighbors and educators to the local doctors and artists. “It’s really special to go outside and see yourself 1,000 times over… and I was always surrounded by our music, with five different Black radio stations on at all times. That’s what shaped me.”

Black music is rooted in the South. It’s where spirituals were born, and where gospel evolved, laying the foundation for all Black music and shaping essentially all genres of American music. This early music was a form of faith and empowerment, which Black communities needed in abundance to survive slavery and the racial terror that followed emancipation. “I even added a little bit about the Fisk Jubilee Singers, and a hint of how HBCUs [Historically Black Colleges and Universities] have been so tied to the Black church.” In 1871, a group of nine young people formed a chorus with the goal of performing and raising money for their newly established Black college, Fisk University. Most of the original group, who became known as the Fisk Jubilee Singers, were former slaves.

Johnson saw it as essential to weave the legacy of HBCUs into the story. “I reflected on my time at Spelman, and the Spelman and Morehouse Glee Clubs. They have such a rich history. And, of course, there’s Fisk. The Fisk Jubilee Singers were traveling across the world in the late 1800s singing for the Queen of England, and building a name for themselves—already showcasing the power of Black music and how it can globally mobilize. The idea is for people to develop a curiosity and unravel the history of HBCUs and the post-emancipation era.”

Moving through the exhibition, Never Turn Back also sheds light on the contributions of Black blues women, who pioneered provocative and radical expression through music. The exhibition’s blues listening station features a “love hurts” theme and includes songs like “Ball and Chain” by Big Mama Thornton and “Crazy Blues” by Mamie Smith. The songs from this era touched on previously unbroached topics in mainstream music like domestic abuse and women committing infidelity. “A lot of these blues women were navigating sexuality and identity. The presence of Black queer women in blues is an important story to tell, because it provides insight into how Black women were thinking about themselves in the 1920s.” This is yet another area where Johnson’s personal identity shapes her curatorial lens. She discussed coming out as queer in her early 20s, and feeling a sense of protection within the breadth of the Black queer community in the South, which she again notes as a privilege. “For blues, I really wanted to also highlight where sacred music diverges into secular music. And blues is kind of an early form of hip-hop where they’re talking about, you know, sex and identity and drinking and smoking. But also the idea that Black people are free now.”

Johnson’s PhD research is grounded in Dirty South Feminism—her Southern take on the modern Black woman, inspired particularly by journalist Joan Morgan’s examinations of hip-hop and feminism. Like many of us, she has a deep love and appreciation for the genre, despite the contradictions it poses for Black women and women in general. She designed somewhat of a crash course on hip-hop sampling for Never Turn Back—illustrating how

producers recontextualized early gospel, soul, and jazz music, creating something responsive to their modern realities while working to immortalize the work of Black artists who came before them.

With an exploration of over a century of history, framed through music, Johnson delivers a moving and educational experience for MoPOP. Her position as the first Black curator in the museum’s history is both a unique responsibility and an opportunity. “It feels like a challenge in a good way,” she says. “There are not a lot of Black curators, just in the country. The reality is that we are not always welcome in museum spaces, as curators, or as educators, or as artists.”

Although the number of Black American curators doubled between 2015 and 2018, they still account for only an estimated 4 percent of museum curators. For Johnson, the confidence and freedom imparted by her colleagues gave her the space she needed to spearhead this project. And the inclusion of her perspective is especially timely at Seattle’s celebrated MoPOP, as Black contributions are tremendous but often the result of marginalization.

“Sometimes pop culture is scary when you are Black,” she says. “A lot of the art is a product of discrimination and exclusion, a product of redlining.” Johnson used the example of Motown, which nurtured the careers of countless artists, from Diana Ross to Marvin Gaye. The iconic record label’s formation and success was the outcome of Berry Gordy’s vision and the supreme talent of the musical acts, but it was also the outcome of the lack of opportunities available to Black artists in the music industry.

Fortunately for Seattle, Johnson sees her future in the museum world and, for now, in continuing to share the privilege afforded to her by her Black Southern roots with MoPOP. She hopes that Never Turn Back will attract more people to the space, particularly new visitors and Black women and girls. “Being in this space allows me to keep talking about Black culture and history in a way that’s accessible. Museums are really great spaces for people to learn from, and I don’t think that I can lean in on that as much, or create as much access, in academia.”

Never Turn Back is on display at MoPOP through early 2027.