This post was originally published on this site

Yeet that cell phone into the sea (or maybe just leave it behind).

The first time I reached the summit of Mount Rainier, in August 2012, I switched my phone out of airplane mode to send a giddy text to the friend who’d helped me train for the climb. As I waited for a reply, I found myself idly scrolling. Through Facebook notifications, no less.

It was just before 7am on a sunny Sunday, and the Mount Rainier crater rim stretched in front of me like a bowl of snow, balanced slightly askew. At 14,410 feet above sea level, I was halfway to cruising altitude for an airliner, atop a volcano—in a place I’d dreamed of standing my whole life. But I’d ended up with my face buried in Facebook’s blue glow. I quickly did a what am I doing? head shake and switched the phone off, a little embarrassed.

Last month, more than a decade later, I stood on a lawn in the San Juan Island County Park with Tiff, a guide for Outdoor Odysseys kayaking company. She explained to the six clients that signed up for the day-long paddle ($149 each) that the operator offered a new digital detox discount: a 10 percent refund if they left their phone in the van for the full six hours.

My boyfriend and I were the only ones to ditch our tech.

Owner Tom Murphy launched the promotion this year to recapture the built-in disconnect that used to come with San Juan Islands kayaking. When he first joined as a guide in 2005, “You could kind of count on shitty cell reception when you went on one of these trips,” he says. But blanket coverage has come to even the waters of Haro Strait, which separate the archipelago from Vancouver Island, and phones get both American and Canadian cell signals. Now that circumstances don’t dictate an off-the-grid experience, Murphy realized it required intentionality.

Phones safely stowed in the van, we carried bright-red two-seater kayaks to the water’s edge and launched into the slight chop of Salish Sea waters. In the paddle north, past exposed rock bluffs and the squat Lime Kiln Point State Park lighthouse, I kept my eyes on the surface for sea life. Oddly, I was ambivalent about the possibility of encountering the San Juans’ iconic orcas; it would be hard to see whales up close and not be able to take a photo.

We all know, in some vague form, that being on our phone is bad for us. Studies have shown that less phone use means better attention spans and better mental health; one recent study showed that 91 percent of people who took a two-week break from phone time saw some form of improvement. What’s more, a 2023 study found that cell phone use went up when people went to urban parks—though it does go down in more remote places like forests and nature preserves.

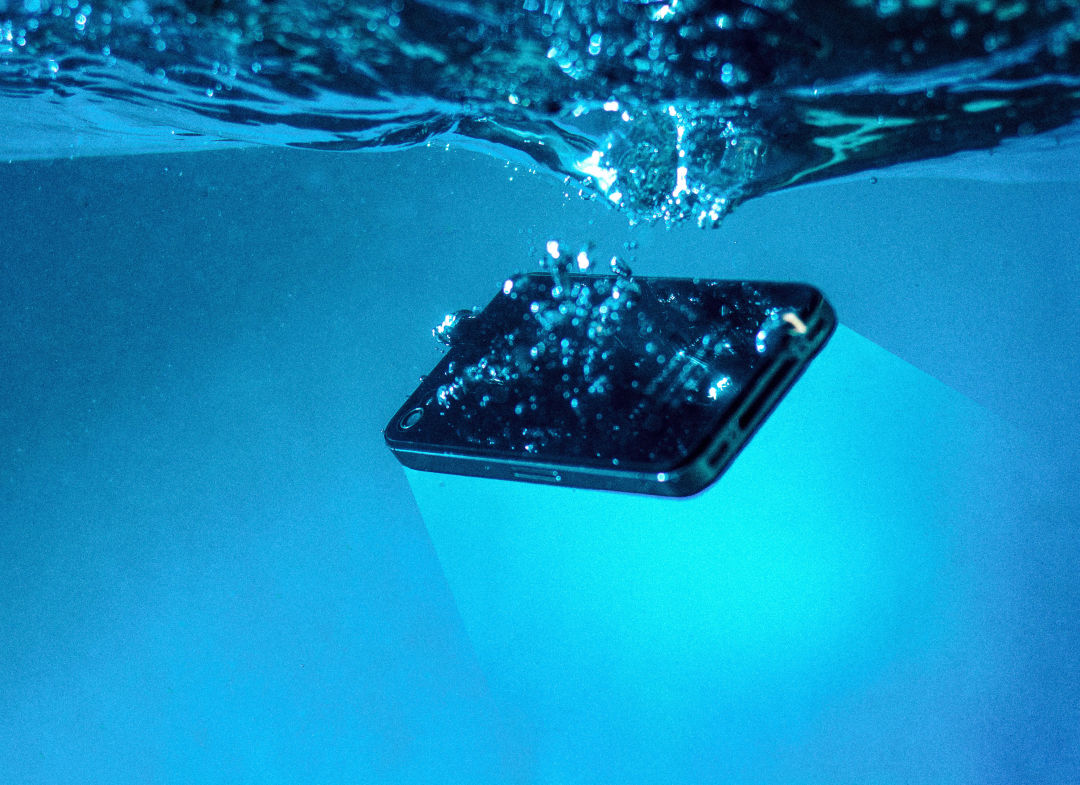

Murphy is pushing the detox because he saw so many people engage through the tiny machines on his kayak trips. (Not, as I suspected, to keep people from dropping their phones into Puget Sound—that hardly ever happens. We hold on tight, not just figuratively.)

“They’re literally there in person, and they’re watching it on a seven-inch screen,” says Murphy. Clients would even edit in real time, using the day trip’s lunch hour to post on social media. “When you could be just enjoying the sunshine and the view and everything else, people are, like, banging their thumbs on that piece of glass.”

Murphy notes that he’s trying to promote disconnection without judgment: “I don’t think people are dumb for doing that,” he says. On my Outdoor Odysseys paddle, we were the only locals, and I knew it was far easier for me to forgo Instagram posts of the stunning but relatively familiar western shore of San Juan Island than it was for the out-of-towners.

Ever since cameras became a main function of smartphones, they’ve been hard to ditch, even in outdoor spaces that we visit specifically because they are undeveloped. Phones are also our navigation tool and our emergency communication; iPhones are now advertised as working with satellites to place an SOS call. Phones quickly evolved from luxury to necessity.

A few weeks after the kayak trip, I figured I’d try a digital detox without the promise of money back. Embarking on a hike on a new-to-me trail just east of Stevens Pass, I stowed my phone so deep in my backpack that I couldn’t reach it. I didn’t start the tracker on my smart watch, and I didn’t even bring my headphones.

For seven hours, I hiked with no GPS data to reassure me how far I’d gone or how many feet I still had left to gain. When the hillsides erupted into brassy red bushes, I took no photos; when we came to a fork in the trail, I dug into my memory of the trail map to decide which way to go. Trudging 4,000 vertical feet back to the car, I had only the ache in my knees to tell me how much of the punishing descent I’d accomplished.

Every time I looked at the view, I implored myself to absorb it fully. Odds are I’ll never get back to that exact spot again (did I mention it was 4,000 feet of downhill?). It was freeing to experience the hike not through the lens of stats and metrics or inadequate cell phone snapshots; I finished feeling full of the actual scope of the mountain.

In the first year of offering the rebate, Outdoor Odysseys has seen more than 65 guests take them up on the offer. About 20 percent of clients are willing to ditch their phones, though guides don’t count digital cameras. (Murphy, an avid photographer, feels that those smaller, less interactive screens aren’t as bad.)

Digital detox has grown into a vibrant travel sector, with The New York Times pegging it as a 2025 trend. While the day-trip discounts at Outdoor Odysseys are advertised on the company’s social media like any promotion meant to bring in customers, sales and marketing director Peter Yacobellis says “there’s no profit motive in what we’re doing here.” People come out of a digital detox trip feeling a little less harried and a little more refreshed; it’s a feeling even more addicting than the Facebook scroll.