This post was originally published on this site

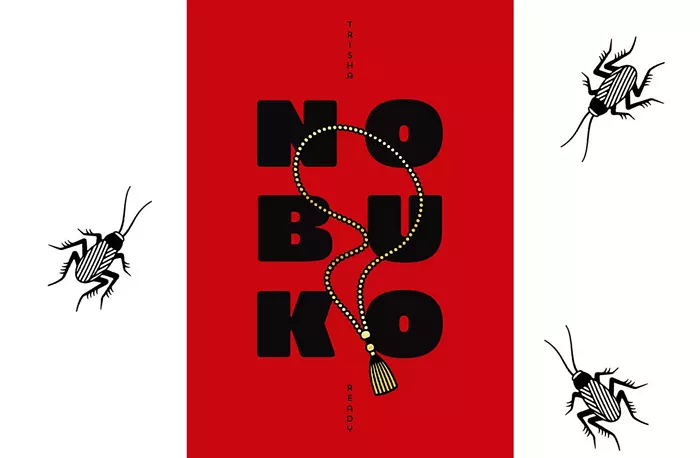

Trisha Ready’s debut novel tells the story of a young American teaching English in 1980s Japan who falls in love with a woman named Nobuko. It’s simple to summarize, but that hardly prepares the reader for Nobuko’s evocative approach in form: 108 ultra-short chapters, each one limited to 150 words.

The book is a modular mosaic that blends fiction, memoir, and prose poetry. Each vignette is its own encapsulated memory that together build a narrative philosophy. And by stripping each scene down to atomic sentences and clear-eyed, judgment-free observations, Ready posits that how you tell a story is an ethical choice.

She wastes no words. “When my plane landed in Tokyo, I realized I had no clue how to get to Utsunomiya. I hadn’t charted a route. Or even located the city on a map.” In three tight sentences—statement, follow-up, fragment—we meet a narrator whose honesty and self-effacing humor are conveyed purely through form. The way she speaks (in plain, staccato beats) reflects humility, curiosity, and openness. From page one, the novel’s style asserts a moral clarity: an insistence on simple, truthful syntax as a guide through an unfamiliar terrain.

While Nobuko’s fragmentary, minimalist approach has roots in Gertrude Stein and American minimalism, its spirit finds equally strong kinship with modern Japanese literature, especially as filtered through English translation. The novel’s restrained realism and episodic structure recall authors like Hiromi Kawakami and Banana Yoshimoto, whose work often unfolds as a series of everyday moments infused with emotional undercurrents. One could easily describe Nobuko in the same terms that the reviewer at A Little Blog of Books applied to Kawakami’s novel, Strange Weather in Tokyo: “a collection of short episodes with little in the way of actual plot,” a story “quiet and understated” and concerned more with “what is left unspoken than what is actually being said.” Ready’s chapters often end not in grand revelations, but in ellipses of meaning: a train ride, a shared meal, a single word of dialogue. She invites the reader to intuit the significance in the silence that follows. This aesthetic shares DNA with the Japanese narrative sensibility that finds drama in the quotidian and morals in restraint.

Early Haruki Murakami is another touchstone: Nobuko eschews Murakami’s surreal flourishes but captures the same gentle alienation and yearning found in his quieter early work. The narrator navigates being a cultural outsider in Japan, and the text mirrors that experience by balancing two traditions. It is at once an American story of self-discovery and a Japanese-style narrative of understated depth, translated into English within the text itself. When a chapter opens with the Japanese word “gaijin!” (“foreigner”) shouted at her, she notes how it was “pinned to me and everyone who hailed from a different country.” The book doesn’t editorialize or over-explain the sting of that word. Instead, by letting it recur at key moments, the accumulation of context turns a simple label into a profound commentary on belonging and otherness.

The magic of Nobuko lies in how its modular structure and rhythmic repetitions produce a narrative far richer than its tiny chapters initially suggest. Each piece is like a compartment. According to Ready’s explanation of her form, “divided into parts, like a bento box is”—each containing scenes or memories. In one section, after weeks of witnessing her boss Kacho humiliate students with a riding crop, the narrator rebels in a moment of deadpan theater: “As he started his staccato spiel on discipline…I ducked under my desk.” The prose remains as measured. No exclamation point required. But through it, Ready creates a beat of moral victory. The meaning emerges not from plot or authorial commentary, but from adjacency: the juxtaposition of a bullying scene and a quiet act of protest.

Nobuko consistently builds significance through echo. A detail in one fragment (the clack of a katana sword, a shared cup of sake, a spider spinning a web) will resurface later, transformed by context into metaphor. Emotions, too, are distributed laterally across the book. A passing mention of “longing for a transcendent union” in one snapshot reverberates when, many chapters later, that longing is left poignantly unresolved. The result is a reading experience that rewards attentiveness to pattern and rhythm. Linked by rhythm and echo, Ready’s approach solves the problem of representing lived time without conventional plot, turning fragments into harmony.

In practice, this means the novel achieves emotional and moral complexity not by grand narrative arcs, but by accumulation and resonance. These carefully spun pieces resolve into a story that feels complete and profoundly human.

Ready has created a work that is accessible in its language and engaging in its vignette-driven storytelling, yet also richly layered for those who listen to its syntax. Nobuko is an invitation to consider the smallest units of writing: the choice of a period or a conjunction, the decision to repeat a word. In this way, Ready’s book joins a literary tradition that spans Stein to Kawakami, affirming that style and morality, form and feeling, are deeply intertwined. A quiet revelation of a novel, Nobuko asks us to find meaning not in high drama, but in the spaces between the words.

Nobuko was released on FrizzLit Editions in August.