This post was originally published on this site

The first time I got punched in the head, I was surprised it didn’t hurt. I was stunned, but I wasn’t in abject physical pain. I remember noticing this as my nervous system, on the other hand, spun out of control. Frantically trying to process what happened, my brain decided that simply freezing was the best course of action.

It was not.

Emily hit me again. This time, with a straight right to the middle of my forehead. She was moving at warp speed, and I was trapped. My feet were lead and my gloves were superglued to my face. My brain, sluggish and overwhelmed, was unable to control my body. Emily landed a quick double jab to my head and a blow to my stomach. Then I heard Coach Manny reminding me to breathe.

Liann Yamashita believes getting in the ring requires confronting the truest and rawest parts of oneself. That’s hard and, at times, painful work, but she keeps returning week after week because she gets “to be in this with a greater community of people.”

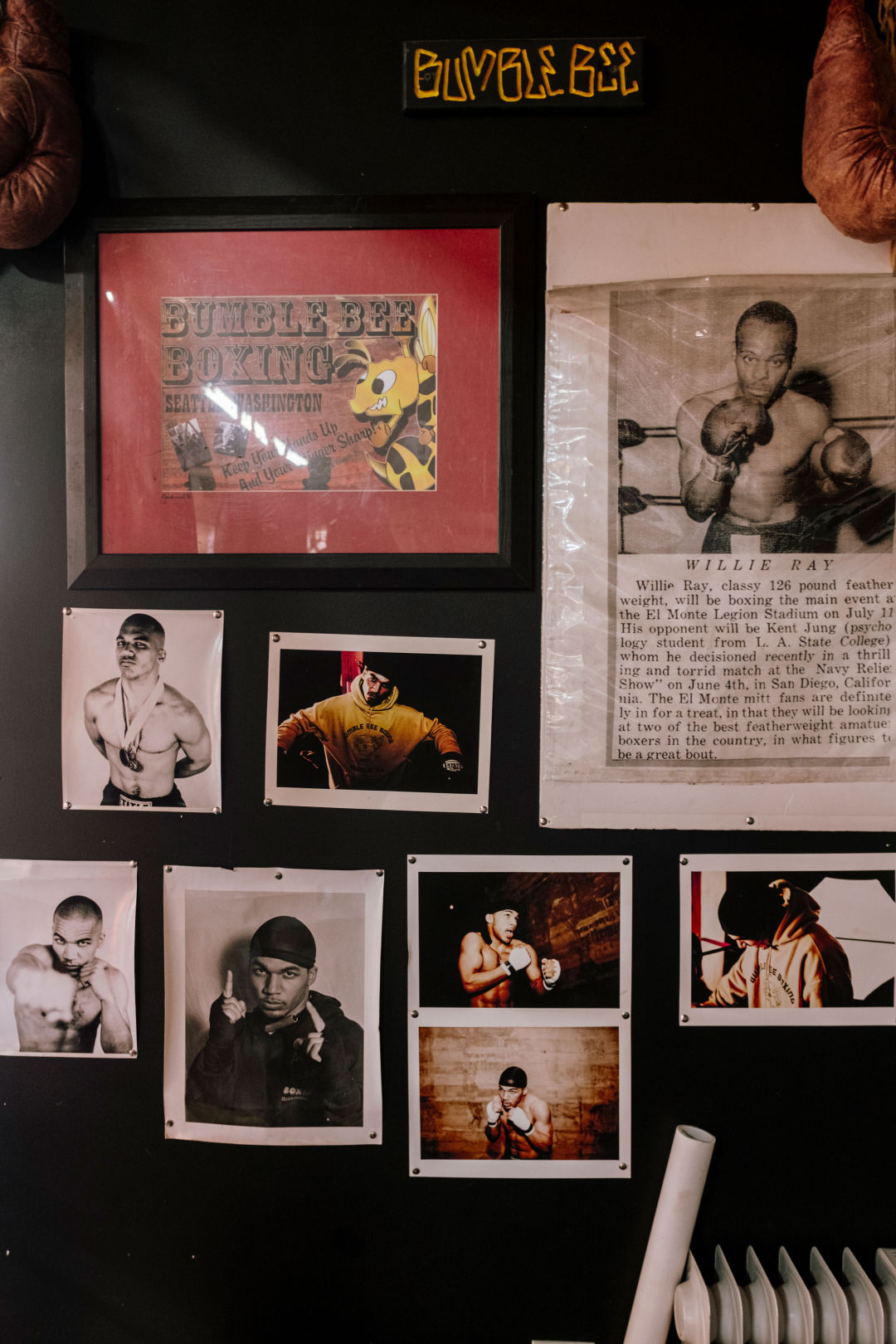

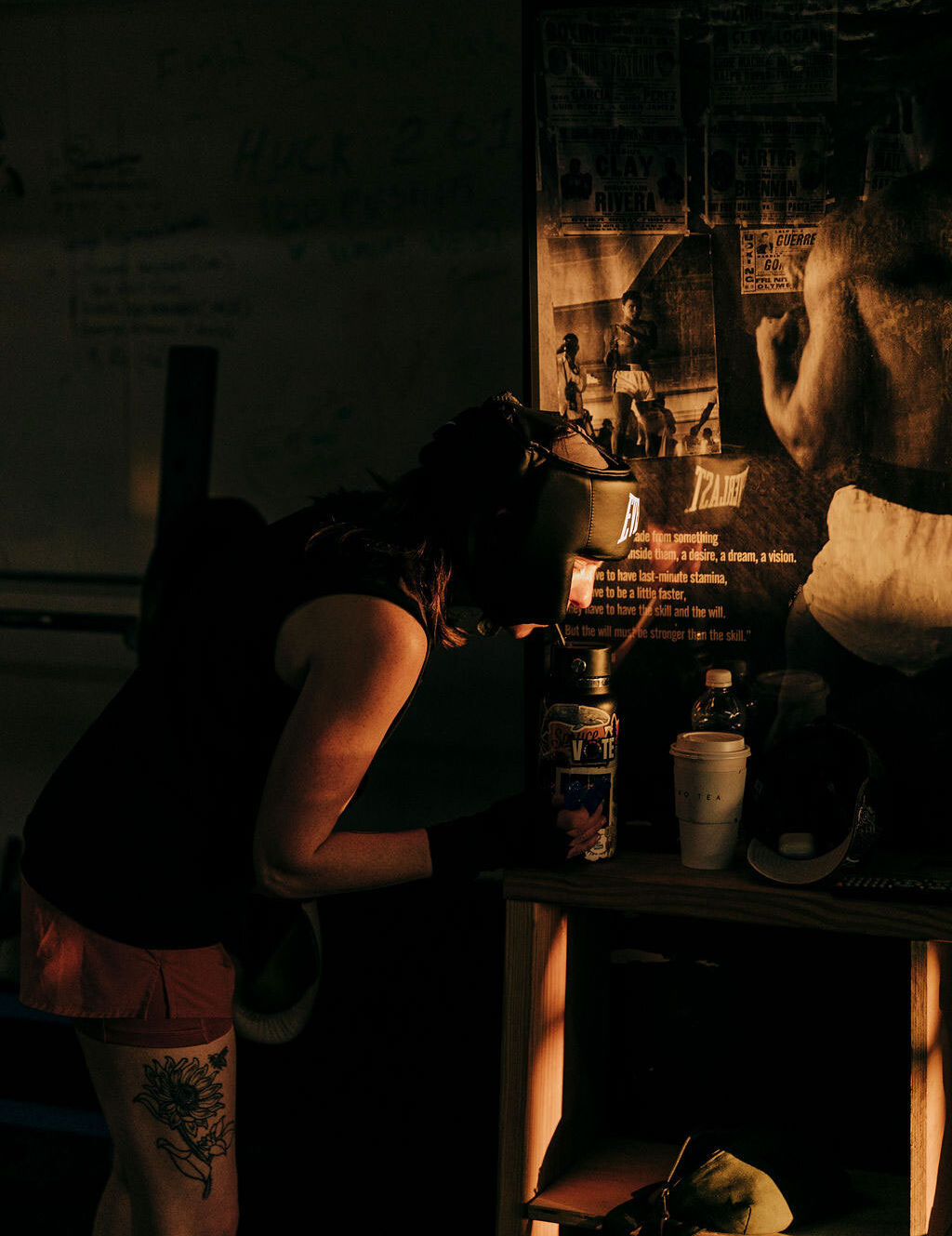

Nomad Boxing Club is a scrappy local gym in Ballard. Heavy bags sway from the rafters, and it smells faintly of old socks and disinfectant. Most of the fights showcased in the newspapers, photos, and posters that paper the walls feature men—Floyd Mayweather, Oscar De La Hoya, Muhammad Ali—but it’s the only boxing gym in the region that offers weekly opportunities for women to spar with other women. Some of these women are on Nomad’s boxing team and actively train for USA Boxing–sanctioned fights. Others, like me, simply show up for the challenge of it and the fierce bonds that form after repeated bouts in the ring. As my fellow Nomad boxer Neal Haley (who’s here battling with Liann Yamashita in the top image, which Manny Dunham watches from the corner) likes to say, “The punching-each-other-in-the-head-to-best-friend pipeline is real.”

After Coach Manny’s reminder, I took a deep breath and tried to ground myself in my body. Sweat pooled on my forehead and what didn’t get absorbed by the headgear trickled down the side of my face. A few drops found their way into the corner of my right eye, and it started to burn. But I heard Neal cheer when, finally, I managed to evade a punch by stepping and then pivoting in the opposite direction—a move I’d practiced a lot and was now able to perform on instinct.

In feedback circles at the end of each night, Coach Manny emphasizes the fundamentals: “Repetition, repetition, repetition,” he reminds us. Repetition bakes the movement into the bones and allows the body and mind to work together so smoothly, the boxer almost doesn’t have to think—the moves just happen.

Breathing connected my brain back to my body. I landed a solid straight right to Emily’s head. She paused, absorbing the punch. Both of us gulped lungfuls of air. When the bell clanged, I hugged her and laughed at the relative absurdity of it all. She was strong and fierce, and I loved her for that. Sparring, after all, isn’t about knockouts or winning. It’s about reciprocal teaching and learning. A punch to the nose isn’t personal. It’s feedback.

I am not a natural in the ring, but I keep coming back. Boxing, more than any other sport I’ve tried, challenges me to regulate the flurry of emotions that flood my nervous system, and shows me how to use my breath to slow things down so I can respond, rather than react. When I can harness this energy and apply it, both inside and outside the ring, boxing becomes a superpower.

It’s hard not to panic when I get punched in the face. But once the two-minute round is up and I can step out of the ring and watch other women spar, I realize there’s more to it than mere surface-level violence. This is one of the reasons I keep coming back. One of my fellow fighters, Liann Yamashita, tells me it’s helpful to think of boxing as “a sport of artistry and science and technique. The really good boxers are the ones who are controlled and the ones who are measured. The ones who can rein themselves in and release themselves in the right direction.” It’s a great goal, but, for me, merely staying present (and keeping my eyes open) continues to be challenging.

Jen Oishi (in Title gear) and Rhea Shinde gear up for sparring. When Oishi first started, she felt like she “got in her head too much” and the bad days in the ring made her want to quit. But she kept coming back and learned that staying loose and playful is key: “Instead of taking [getting hit] as, Oh my God, I’m horrible, I take it as this is a lesson and remind myself I’m learning something right now.” She says that joining the Nomad team was one of the best decisions she’s ever made.

Neal Haley (above) started boxing eight years ago for fitness. Then, about two years ago, she started training consistently with the team. She also serves on the board for the nonprofit arm of the gym and teaches classes. Sparring nights are still challenging for Haley, too. The ring is a panic-inducing space, and she admits that when she first started sparring she was just “getting beat up for a year.” But when she thought about quitting, teammate Peiji Wang took her aside and asked, “What happens if you just stick with it?” Like Oishi, Haley realized getting frustrated doesn’t help. Since there’s always more to learn with boxing, she focuses on fine-tuning her technique. “Execute the movement, not the opponent,” Coach Manny reminds the team.

During feedback circles at the end of the night (pictured below), Coach Manny asks the boxers to share what they noticed about each other’s technique in the ring. The conversation is a mix of pointing out what worked and what didn’t. Billie Thorndycraft (pictured above) believes boxing is a sport that requires this kind of vulnerability. “You don’t get good,” she tells me, “unless you accept that you suck.” She thinks this is especially hard for women to accept: “There’s lots of reasons there’s no women in this sport, but a big reason is men suck when they come in and they learn because they’ve been given permission to learn. But women come in and they suck and they think that it’s some failing of character, as opposed to an opportunity to grow.”