This post was originally published on this site

Centuries before haunted house attractions or horror films, audiences thrilled to magic lantern shows. Also known as phantasmagorias, these performances featured hand-painted glass slides illuminated by candles, projecting fantastical and macabre images—grinning demons, bleeding nuns, the political dead—onto darkness or thick smoke. By the 1790s, phantasmagorias had become true multimedia spectacles: images rose from the floor and disappeared, thunder crashed, and disembodied voices echoed around the room.

Manual Cinema, established in Chicago in 2010, makes work that feels like the phantasmagoria’s great-great-grandchild. The group’s central technology—the humble overhead projector, the kind you might remember from school—functions like a magic lantern, casting silhouettes, cut-

paper shadow puppets, and colored slides aglow and transforming them into something otherworldly.

“When I’ve seen it, I’m like, this is magic. I’m a practitioner of it, and I don’t fully understand it,” says Drew Dir, Manual Cinema’s co–artistic director and lead puppet deviser. He’s inspired by very, very early film, such as the work of Georges Méliès, the French magician and filmmaker who made the moon stick out its tongue in 1902’s Le Voyage dans la Lune.

But a Manual Cinema show is more than just eerie shadows. There are live actors, props, and an ensemble of musicians creating a live score. Watching a performance has a choose-your-own-adventure quality: “It’s like watching an animated film be created live in front of you,” Dir explains. “Audiences can either watch the final image that we’re making, the shadow play on a big screen above them… or they can watch all the craft that is being put into making that live below, because we expose everything.”

Manual Cinema got its start about 15 years ago, thanks to a spare overhead projector in Julia Miller’s landlord’s garage. Miller, another of the company’s five co–artistic directors, had experimented with shadow puppetry as part of Chicago’s famed-but-now-defunct Redmoon Theater. She brought a small group of artistic friends together—some with backgrounds in theater, others in music or visual art—to make a short shadow puppet show inspired by a lullaby. The result was Lula del Ray, which Dir describes as a “dreamy space-cowboy story about a girl growing up in the middle of an array of radio telescope satellites in the desert who hears this song, this far away song, and goes on a journey to pursue the song.” The project was meant as a bit of a lark, but after its performances at a storefront theater in Chicago, “people started asking us, ‘When’s your next show?’ And we said, ‘We don’t have a next show,’” Dir says.

Until, of course, they did. The group fell in love with the possibilities of the form—the chance to combine storytelling, puppetry, music, spectacle, and movement. They took Lula del Ray’s dreamy space-cowboy ballad to bars and DIY spaces in Chicago. The next year, on Halloween, they premiered a show called Ada/Ava in the front window of Dir’s apartment building. They’ve since toured Ada/Ava around the world, and followed it up with more than two dozen other works, an Emmy, animations featured in the 2021 Candyman remake, and a tour with folk-rock band Iron & Wine.

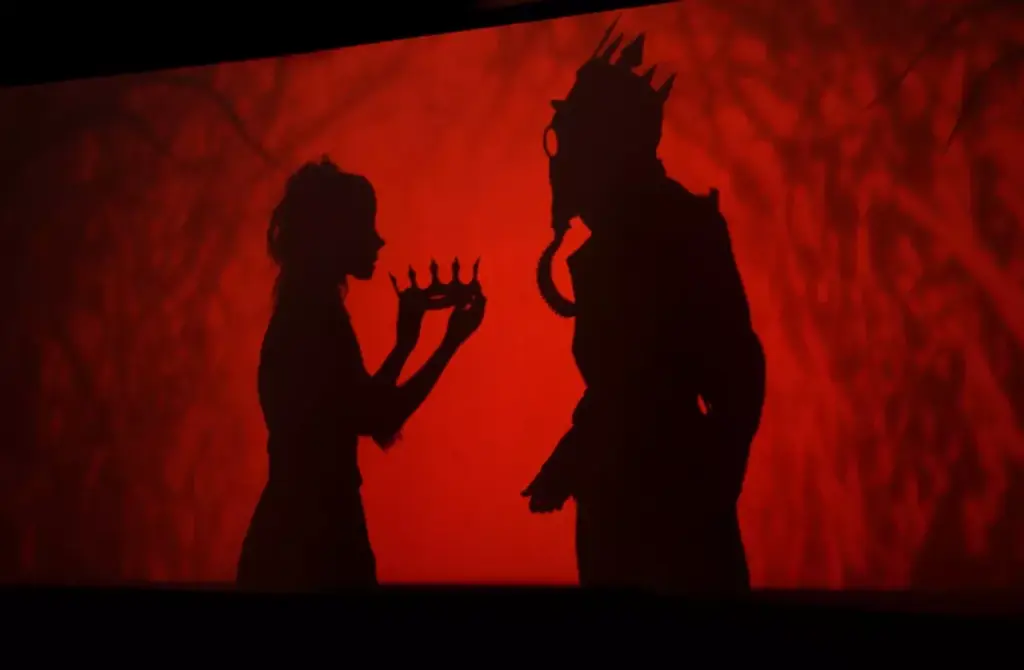

The 4th Witch—which they’re bringing to Seattle in mid-November—is inspired by elements of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. But don’t expect a straight retelling. Dir describes it as a “mirror image story of Macbeth,” in which themes of power, magic, vengeance, dreams, nightmares, and guilt “play out not on the psychological terrain of Macbeth, but for an unnamed girl who is at the opposite end of the spectrum of Macbeth [himself] in terms of her power and her status.” The story follows a young girl who flees a war-ravaged village and escapes into a forest. There, she’s taken in by a witch and becomes her apprentice. Her grief makes her magic more powerful—and soon, her rage finds a target: Macbeth himself. “We have a character in the form of this girl who undergoes an enormous trauma and is offered power to right that trauma,” Dir says. “But the moral content of that power, I think, is ambiguous.”

It’s one part war and one part witches—two ways of solving problems, perhaps. And if the heavier themes are the meat of the show, Dir says the witchcraft is the dessert. After all, there’s a reason why “people have been attracted to Macbeth for centuries,” he says. “There’s all sorts of opportunities for spectacle, with witches, magic, and the creation of potions, and flying. There are all sorts of tricks that we were excited to take on.” (Even the score, featuring three female vocalists alongside piano, violin, and cello, sounds appropriately witchy.)

That excitement came only after years of resisting the idea of doing Shakespeare. “We always said, well, [Shakespeare] doesn’t really make sense for the work we do. We’re so visual and nonverbal and Shakespeare is so much about the language.”

But the company eventually found what Dir calls a “backdoor” into the story: “I began to think about it in terms of not lines of dialogue, but all these symbols that recur over and over and again in Macbeth. You can really distill the play down into this very simple visual vocabulary: a witch, a dagger, a bloody hand, a crown.”

The artistic team also had some unusual partners in crafting the show: the puppets themselves. “We say all the time, what does the medium want? Or what do the puppets want? Because oftentimes we’ll come in with a story, but we’ll find that the puppets want to tell a different kind of story, and it’ll be a negotiation.”

Disturbingly, what the puppets wanted here was revenge. That wasn’t in the seeds of The 4th Witch when they began work, says Dir. “But there was something about this story about this girl who is responding to personal tragedy… her grieving process translates into a desire for revenge. And that was something the character, the silhouettes, the puppets wanted to do.”

He likens discovering what the puppets want to using a metal detector on a beach. “You might go in with a plan of what you’re looking for, but the metal detector, if you point it over here, it goes, beep, beep, beep, beep. And you just have to follow that because you know something is there and you don’t know what it is, but this thing is beeping and you have to move towards it.”

For all the talk of puppet agency, this is still very much art made by humans. “In our daily lives, we’re surrounded by so much imagery, and most of that imagery comes from corporations that are crafting it because they want you to buy something,” Dir says. “Increasingly, the imagery is coming from machines that are creating without much human input or craft at all, or that are just copying or duplicating images that are [already] out there. And so to be able to offer an audience a certain kind of imagery where you can feel the labor, you can feel the material, you can feel the hand, the human hand behind it—I think increasingly we don’t have that experience, and it can be almost an emotional, moving experience to see an image or art that is crafted that way. I think we’re in danger of losing touch with it.”

“The value of Manual Cinema, the name of our company, means literally cinema by hand,” he adds.

The experience is emotional—when Manual Cinema’s Frankenstein played at the Moore for one night in March 2024, I exited with a tear-streaked face, and the bathroom was full of women visibly moved by the performance. (This also might have had something to do with the emphasis on motherhood and grief in the show’s retelling of Mary Shelley’s story, an angle well-suited to Shelley’s own biography, which involved a mother who died shortly after giving birth to her, and multiple miscarriages—one so awful she might have died of blood loss had her husband, the poet Percy Shelley, not told her to sit on ice.)

Gruesome anecdotes aside, it’s remarkable that a performance where all the wires are showing can evoke such strong feelings. It’s further evidence that the power of art lies not in technical mastery, however impressive, but in its ability to show us other humans grappling with age-old themes: love, loss, power.

And even with everything visible, the show feels like magic, just as in the phantasmagorias of old. Maybe that’s the real secret—even when we know it’s all a show, we can still choose to believe.

See Manual Cinema’s The 4th Witch at the Moore Theatre on November 12, 7:30 pm, all ages.