This post was originally published on this site

“If you were wondering what the poem meant, I have no idea,” Patti Smith offered, after reading Rimbaud’s “Genie” on Monday night at the Paramount Theatre. “But, to me, it just means everything.”

This is exactly how I feel about Horses. I know from a decade of obsession over Smith where the songs come from: “Redondo Beach” was inspired by a newspaper headline, “Break It Up” was taken from a dream she had where Jim Morrison breaks out of a marble statue, and “Elegie” was written after the death of Jimi Hendrix. But none of these concepts can really explain what Horses is about. The songs exist outside of reality, time, space, and logic. Yet, to me, they just mean everything.

While “Redondo Beach” and “Gloria” have soundtracked (via my earbuds) many moody walks down the hallways of my high school, I’ll admit that Horses did not fully click for me until I was in college. What changed everything was a last-minute decision to see Patti Smith perform Horses in its entirety for the 40th anniversary back in January of 2016. I remember sitting in one of the last rows at the Moore Theatre, where the air was hot and sticky and my naked eye could just make out her iconic silhouette. Despite this, her voice echoed up to me like a roar from a wishing well. That night, I felt my understanding of art, language, and identity expand. While it’s hard to believe that the show took place a decade ago, over the weekend I noticed that the shirt I bought that night (which is still in my regular rotation) now has a hole along the collar. It’s time for a new Patti Smith shirt, and thus, it’s time for another Horses anniversary tour.

Just as she had 10 years ago, Smith walked out on stage in her signature ensemble: shaggy, loosely braided silver hair, a white t-shirt, and a black blazer. She swiftly began singing the album’s opening line, “Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine,” as fans stood up and shouted along. I immediately noticed that Smith’s voice sounded stronger than ever. Her ability to switch from a punk growl to a sweeping belt is overlooked. Yes, she’s an amazing poet, performer, and memoirist, but she’s also an incredible vocalist with unbelievable control.

With each “G-L-O-R-I-A,” I felt my former 19-year-old Patti Smith-obsessed self rise to the surface until I was bubbling over. I had entered the show as a worn-out 29-year-old on a Monday night, stressed about parking, but I was soon reminded of how important this woman has been to me throughout my adulthood; a large Patti Smith poster hangs near my desk where I work. Her poetry books and memoirs crowd my bookshelves. Her albums and bootlegs occupy a large chunk of my record collection. I can recite her spoken-word pieces, like “Birdland” and “Piss Factory,” from memory. I began scheming how I could rush to the front to grab a setlist at the end of the show. Then, like a recovering addict, I thought, “No, Audrey, those days are behind you.”

Smith sang through the tracklist of Horses with minimal chatter in between songs. After “Free Money,” she directed the audience to carefully turn the record over to side two, “or, if you’re like me, just slam it onto the fucking turntable.” She played an extended jam of “Land: Horses/Land of a Thousand Dances/La Mer(de),” wailing and shaking like I had seen her in clips from the ’70s. In a daze and out of breath, she left the stage, forgetting to play “Elegie.” “That’s never happened before,” Smith admitted after returning to play it for the encore. “I guess it was just the thrill of the moment.”

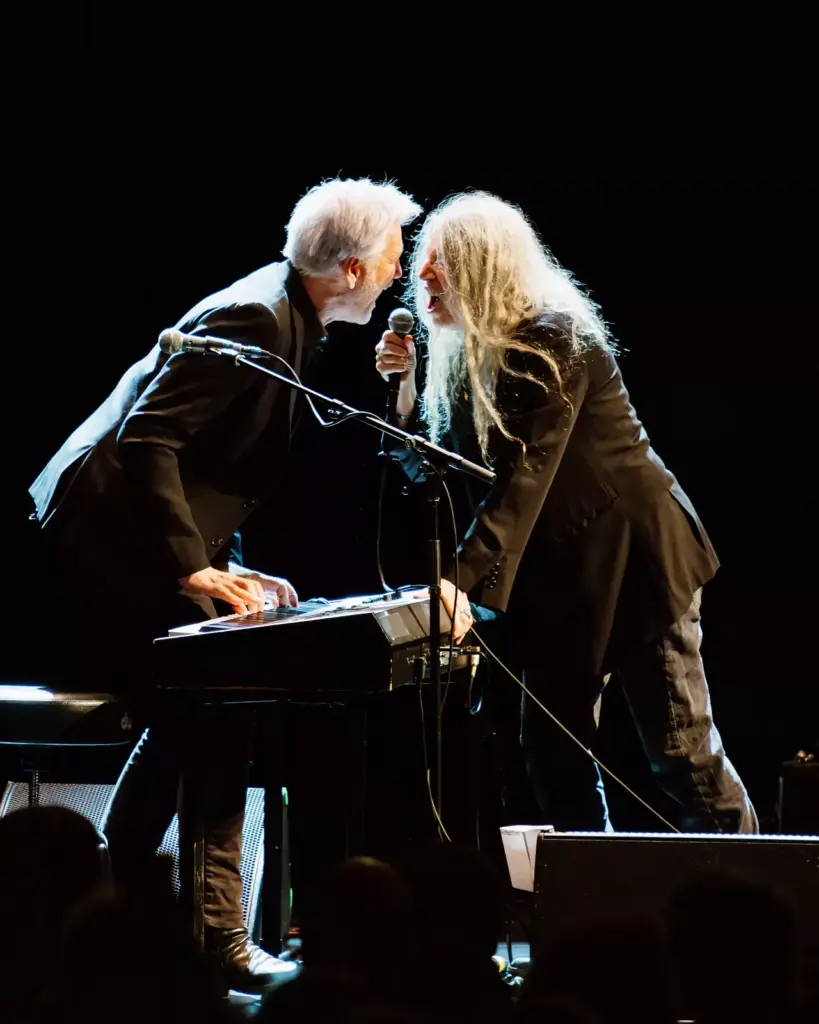

While Smith recovered backstage, her band—consisting of original members Lenny Kaye and Jay Dee Daugherty, along with keyboardist/bassist Tony Shanahan and her son, guitarist Jackson Smith—played three songs by Television, “See No Evil,” “Friction,” and “Marquee Moon.” While some fans looked at each other confused, others used this as an opportunity to refill their drinks and use the restroom. A few exuberant fans stood up in excitement as they played “Marquee Moon.” Smith and her band’s relationship with Television is well documented—they grew out of the same wave of New York punk, and frontman Tom Verlaine and Smith dated in the mid-1970s and remained friends until his passing in 2023.

Smith returned to the stage with a mug of tea and her blazer replaced by a loose tuxedo vest. As she began singing “Dancing Barefoot,” the audience rose and collectively began dancing Stevie Nicks style. While I cringed as a woman in one of those hats began swaying and moving her fingers like she was casting a spell, it was actually beautiful to see what that song does to people. Looking around, every fan was dancing as though they were completely alone and embodying the most carefree version of themselves.

Taking a moment to revisit the exact day, 50 years ago, Smith explained that Horses was meant to be released on October 20, Arthur Rimbaud’s birthday, but was delayed because of the 1973–74 oil crisis. “I’m sorry, darling, but it can’t come out on Rimbaud’s birthday because of the [oil] shortage,” Smith said, impersonating what Clive Davis had told her. Smith expressed that she was disappointed, but delighted to hear that the new release date was November 10—the anniversary of Rimbaud’s death. In honor of the French poet, Smith read one of her favorite poems by him to a crowd of mostly silent fans. (I say mostly, because a drunk person was rambling loudly, which was then made worse by a sea of angry “Shh!”)

I was delighted as the band began “Pissing in a River,” a favorite of mine from her sophomore album, Radio Ethiopia, which, again, displayed the full range of Smith’s vocal abilities. Afterwards, Smith introduced the lesser-known 2003 song “Peaceable Kingdom,” explaining that the lyrics came out of her concern for the plight of the Palestinian people over two decades ago. “We wrote it in the hopes that things would get better,” she said solemnly. “I’d like to sing it tonight for the Palestinian people, with all of the sorrow, hope, and care that a human being can muster for those they’ve never met but feel and have always felt love for.”

Waving goodbye to the crowd as she finished singing “Because the Night,” Smith and company returned for the encore, dedicating “Elegie” to Jimi Hendrix, as well as the 29 crew members killed on the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, which sank on the same day that Horses was released in 1975. “People Have the Power” closed the show as expected, leaving the audience all riled up and ready to make change in the world—or so Patti and her late husband Fred had hoped when they wrote it. “He hoped that it would excite and incite people to march and to use their voice.”

I left the theater without fighting anyone for a setlist or waiting to ambush Patti Smith at the private exit. Instead, I purchased a signed copy of her new book, Bread of Angels: A Memoir, to add to my collection.

Pattisims

“Tom Verlaine and I lived in a six-floor walk-up in the East Village. Tom liked to wake up a little later, so I would go down six floors and get him coffee and chocolate donuts, which was his favorite breakfast.

“Excuse my language—I’ve been in New York for a while and [‘fuck’] just means ‘poop’ over there.”

“All I want to say is, thank you for the battery. I was feeling a little bit like that rabbit, you know, winding down.

“I’m not saying this in a bragging way, but every once in a while, someone will say, ‘Oh, Patti, Horses changed my life,’ but I have to say, this fella, Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith changed mine.”

“You won’t believe this—actually, you will because you were here, you were witnesses—but I actually forgot to put one of the songs on the [Horses tracklist]. I just breezed past it! I’ve never done that before, but I guess it was just the thrill of the moment.”