This post was originally published on this site

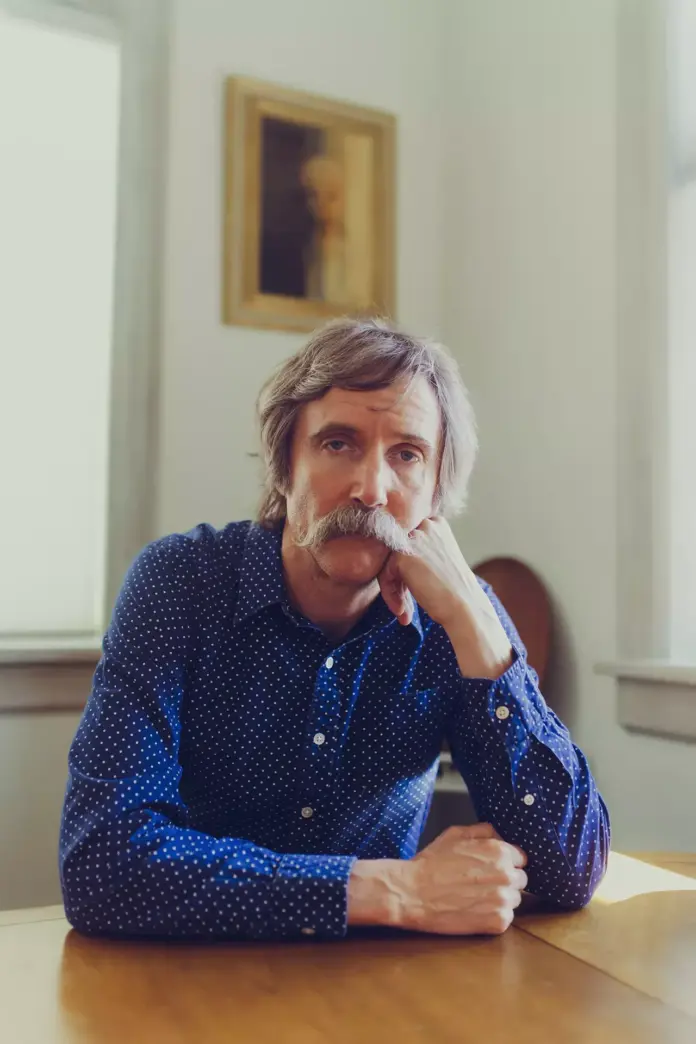

Dean Johnson says that there are some pretty mean songs on his sophomore album, and that’s why he’s titled it I Hope We Can Still Be Friends. However, the name alone should tell you that he’s far from a bully. The man is soft-spoken, hyper-considerate, a little self-conscious, and impossibly charming. When I arrived at his house on a sunny Monday afternoon, he was anxiously awaiting my arrival with the tea kettle whistling and two types of tea neatly set out for me to choose. As I debated whether to choose decaf or herbal, I remembered what a friend recently said to me in preparation for the interview: “Everyone who meets Dean falls in love with him.” It’s easy to see why.

Johnson’s music is warm and laid back with the wit of Michael Hurley and the vocal stylings of the Everly Brothers. His presence radiates gratitude, and he appears to be genuinely astonished that people listen to his music. This magical combination of talent and sincerity has led him to tours with Rilo Kiley/Jenny Lewis, Blind Pilot, John Craigie, and more; he also signed to Saddle Creek this year—I Hope We Can Still Be Friends will be his first release for the label. I caught up with Johnson at his home in Seattle to discuss his new album, finding his voice in his 40s, and the overrated concept of dream jobs.

I know that your debut album included songs you had written over a long period of time. Is the same true for I Hope We Can Still Be Friends?

That is true. At least a third of the songs, I never thought I would record. I had enough friends who wanted me to record them, so I did. And for my own sake—to give them a place, you know? I kind of dread the idea of recording, but I ideally want to embrace it and have that be more of the focus of what I do. I have a lot of music to record.

Going onstage and singing my songs can still feel awkward. If you’ve ever heard the songs on my first record, there’s a lot of heartbreak—exposing stuff. They can be exaggerated, but they are all written in the first person. There is stuff about jealousy and possessiveness. Doing those solo can be pretty vulnerable.

As you were choosing which songs to record, did you find a unifying theme on the album?

Yeah, I did. The second single, “Death of the Party,” is about energy vampires, and it’s the most overtly mean song. There are other prickly songs on the album, mostly about relationships. There is a kind of heavy “mean” theme. It’s a little bit embarrassing how petty some of them are.

I have a hard time with people who are relentless talkers. When I sing “Death of the Party” to audiences, I say, “I hope you’re not afraid to come and talk to me after this song!” That is actually what led to the title I Hope We Can Still Be Friends.

What is your favorite song on the album?

My favorite is called “Shake Me.” It’s about revenge from Mother Nature. The destruction of the planet might be where humans eventually find common ground. The lyrics are “mountains under carpet,” and I always explain that line before I play it live. It’s about sweeping all your problems under the rug. A lot of the songs feel fragile on the record because we were playing live and weren’t very rehearsed. There is a delicacy to the recording. It’s a little bit wonky. “Shake Me” goes off the rails a little bit. But hopefully, that adds to the charm.

What musicians do you look to for inspiration?

I feel like I’m pretty typical when it comes to influences. Early on, I got into Bob Dylan, the Beatles, and Neil Young. Then, I was really into Sam Cooke and Ray Charles. When I was in high school and middle school, I loved the Violent Femmes, the Dead Kennedys, the Cure, and Echo and the Bunnymen.

But there are some songs that make me want to write. Like Neko Case’s song “Star Witness.” That is an incredible song. Her songs paint a strange picture that feels like the Pacific Northwest to me. I think she would have been a great person to soundtrack something by David Lynch.

I’ve noticed that much of the press about you puts an emphasis on your age. How do you feel about that?

Well, it doesn’t bother me if it comes up in an interview because my story is unusual—I released my first record [Nothing for Me, Please] at 50. I can’t blame anyone for drawing attention to that. I can have times when I wish I were 22 years old and the life of the party. I can feel self-conscious. But it’s just me, really. People are mostly nice.

I can tell that touring is good for my brain. I used to have a really good memory. It’s sad that I’m doing this at this stage in my life when I can’t remember things as well. If I were doing it at 25 or even 30 years old, I would remember every face and every name. I’ve lost that big time. That feels kind of crummy.

Where do you see your career headed?

Good question. At least right now, my booking agent and my manager are trying to get me to grow as much as possible. But having a big team seems like a significant challenge to me. Being immersed with other people 24/7 is a potentially precarious situation. My biggest goal is to enjoy the recording process more than playing to thousands of people. However, I make more memories on the road than just sitting around the house and keeping a routine life. My routine life is extraordinarily bland. Taking a walk with my girlfriend Kate is my favorite thing to do.

If you recorded albums when you were younger—let’s say 25, 35, and 45—what would that have sounded like?

They probably would’ve been more indie-rock adjacent. I think I would’ve sung a lot differently—even in my 30s. I am still learning how to sing. I just had two shows in a row where I was cringing at myself the entire time. I’m not good at remembering to breathe and relaxing my diaphragm.

In my 20s, I probably would’ve belted a lot, and not in a controlled way. I probably just would have been loud and more obnoxious. I’ve made recordings at home in the last 10 years that are pretty bad. I like to think that if I were making albums in my 20s, I would’ve learned some of the stuff I have learned over the last few years a lot earlier.

I did not get comfortable onstage until I was in my 40s. In my 30s, I was pretty shy onstage. To this day, when people post videos of me playing, I don’t like to listen to them, but I think that’s pretty typical.

Do you come from a musical family?

Neither of my parents played an instrument. They gave us children an organ, hoping one of us might pick it up, but that never happened. My brother, who’s eight years older, got me a cheap old guitar when I was 14 and showed me the basics. Over the next 15 years, I just noodled with the guitar. The typical path is to take lessons and learn other people’s songs, but I mostly just made up guitar parts.

The only other unusual thing about my childhood was my dad; he was home a lot and sang all the time. He was an incredible singer, but my siblings and I hardly acknowledged it. It was just normal to have him sitting at the table singing songs from opera to Ray Charles to the Beatles to Bob Dylan.

Otherwise, my parents barely played music when I was a kid. My younger brother and I were accidents and born long after my older brother and sister. Most of our childhood, we were just hearing what our older brother and sister played, and it wasn’t even very much of that.

When you were a child, what did you foresee your adulthood being like? What path did you see yourself going down?

I didn’t think about it… The longest job I ever had was as a carpenter. I was a bartender for 11 years. I’ve done handyman stuff. I’ve made coffee. I never got myself on the trajectory of having a career.

That reminds me of the quote “I have no dream job, I do not dream of labor.” Outside of a career, what was capturing your imagination or interest as a child?

[Laughs] Yeah. That probably relates to me. Music has been the only constant—me, connecting with the guitar. I never became much of an artist, but I also love the art world.

What’s the most memorable live show you’ve played?

The biggest one was last summer. I was invited to play Roskilde, a huge music festival in Denmark. Our slot was at noon, and it was pouring rain. Plus, it was the last day of the festival—people had partied their brains out. Nobody knew who I was, of course. We were playing in an indoor space that had 1,200 capacity. I thought we’d be playing to 50 people.

Anyway, we came out of the curtain from backstage and the place was full to the brim. We were like, “Holy shit.” Luckily, I relaxed and had a great time talking to the crowd and making jokes. The crowd was dead quiet during our set, and then the applause was rapturous. I kept laughing because of how thunderous it was. It still blows my mind.

What was the first concert you attended?

Around 1985, when I was 14, my older sister was dating a guy who was the most influential music guy in my life. He was into Seattle bands. I went to a Young Fresh Fellows show under his wing. That was a big deal. Another time, that guy’s brother took me to buy my first electric guitar. It was really special. He also took me to see the Dead Milkmen at the University of Washington HUB Ballroom when I was about 15.

Going to see live bands gave me a very particular feeling and energy—a very nervous energy. When I turned 21, I used to go watch open mics at bars, and I would get so incredibly nervous on behalf of the performers. I was nowhere near performing.

It is interesting to hear you’re a bit self-conscious about your singing because anytime I’ve ever heard anyone talk or write about your music, there’s an emphasis on how beautifully you sing. You are often compared to the Everly Brothers.

And that’s absurd! Maybe I’m like a very unrefined back-porch Roy Orbison. I feel so unrefined compared to people who are natural singers. I can’t control my vibrato. Sometimes I’ll get a really nice flow of vibrato, but I still haven’t worked hard enough to figure out what the hell is going on.

Although, as I’ve gotten more experience, I’ve begun to enjoy performing. I enjoy the singing part a lot. I feel really fortunate and absolutely grateful that there has been any attention to my first record and that things have happened like this. When I recorded that album, I imagined that I probably would never release it.

I wouldn’t have gambled any money on getting this far. And, considering my age, the fact that Saddle Creek wants to release my music means a lot. I feel like because of my age, it feels like it’s more authentically the music that’s appreciated, and I like that.

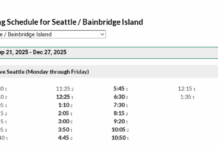

See Dean Johnson at the Showbox on November 21, 7pm, 21+.