This post was originally published on this site

I was recently asked about my favorite flower. Jasmine at night in Los Angeles returns me to myself, across time. That smell anchors me in a personal ancestry specific to California.

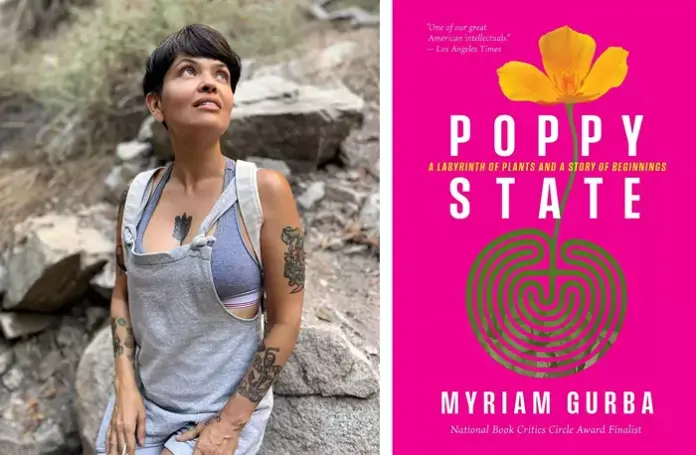

Poppy State is Myriam Gurba’s labyrinthine creation through California’s plants, expansive markers and partners in her life, and the book itself, while it refuses the cliched delusion of catharsis so commonly found in American memoir, does offer a kind of return and a clearing.

“California is many things to me,” Gurba said, when we spoke. “Beyond this political entity with these arbitrary borders that we call a state that is governed by an asshole named Gavin Newsom. It’s a spiritual state, but it’s also the land, and all of the life that is sustained by the land herself.”

And it’s long sustained her.

“I remember being on the playground [as a child] after it had rained and thinking that California smelled so delicious that I should probably put her in my mouth. Because if she smells this good, she’s probably gonna taste even better, right? And when no one was looking, I would collect rocks and put them in my mouth, and then suck the flavor out of them, like, concentrated California.”

Gurba has written many books, including Mean (a true-crime memoir), and Creep, an ambitious essay collection that successfully takes on the concept of oppression through cultural commentary and personal essay, calling out a past abuser, the United States itself, and many historical events and cultural figures in between. Creep, while as funny and fast as any she’s written, is heavy and dark with violence in its many forms. Poppy State reads like a progression and expansion of the experience and perspectives in Creep, explored through her distinct voice and style, defined in part by something she calls textured writing.

“By texture, I mean that when your eyes move across the page, you have a tactile experience, because there’s so much care in word arrangement, the visual, as it’s represented,” says Gurba. “When I consider texture, I then start to think, stylistically, what would help me to achieve the type of texture that I want to represent?

“With Creep, I wanted to lead readers into a sort of fog without them knowing that’s where we were going, then just sort of push them into it. Typically, essay collections begin with the title essay, but I inverted that so that readers arrive [in that fog]. Rather than putting them on a journey toward enlightenment, it’s a journey into confusion.

“Poppy State continues that journey of confusion. I wanted to create a structure that would both confuse, but also contain, which is why a maze or a labyrinth came to mind. We could say that Poppy State is my exit from that fog into forests and valleys and deserts. So we’ve left this landscape where I can’t see my own hand when I extend it in front of myself. Now there’s this openness, and I’m able to interact with the land.”

In Mean and Creep, we witness sexual and physical assaults at the hands of men Gurba has escaped and survived. In Poppy State, the primary male figure is her father, and while she says he’s not perfect, she creates a glowing portrait of him. There is peace made in these pages, and it was surprising to me as a reader not to get any daddy shit talking. It was refreshing and powerful, which is typical of her.

“As my relationship to plants was deepening and working to heal me or to revive me, it became undeniable that the relationship I had with plants was entirely facilitated by my father. So, for all of his faults, and for all of the mistakes that he made raising us and in his role as a patriarch, I wanted to honor what he had gotten right. The two things that he most got right in my life are, one, the relationship that he helped me to establish with the earth, especially through plants. That’s going to sustain me for the rest of my life, and I relate to my father now through plants. He also introduced reading into my life—a fundamental part of who I am, and I have to celebrate him for that. That he taught me to read, and the fact that he taught me to garden, go together. I see them as intertwined.”

As multifaceted as this description of a relationship may be, the narrator of this book comes across far more complex as she grows and outgrows one situation, relationship, and life after another. I had to ask her how many selves she included in this book.

“You could say that I’m many people, in that many people are also plants. Because in this [book’s] world, a person is also a poppy. And in this world, a poppy flower is also corn. And in this world, corn is a vegetable, and in this world, vegetables are also books. And then there’s the notion of my lost soul, and where is she? Is she in this construction as well? Or has she left the building?”

This is a book about getting lost in order to be found. It’s a book that reaches for a spirituality that refuses containment. I also wondered if Gurba was using this book to cast spells, even specifically on her readers, because of certain patterns and repetitions that few readers would miss. This led us to a rich discussion about her spiritual practice in Santería.

“The prose is written in a way that is intended to be incantatory, which it does through rhythmic accretion,” Gurba says. “You mentioned three and five appearing frequently in the book. I am what is called an aborisha, meaning that, in Santería, an Afro-Cuban religion, I have received a set of spirits and warriors. When you receive these warriors, it means that you’ve received a set of protective spirits, and these spirits dwell in your home, and you have to care for them. The primary warrior is Eleguá, and Eleguá’s number is three. Eleguá clears obstacles from one’s path…I am always asking him to remove whatever obstacles need to be rolled out of my path. He’s one of my favorite orishas. Orishas are, like, these divine messengers to God.

“The number five emerges because there is that scene in the book where I’m ordered by a priestess to make an offering to the goddess Oshun, who is a protective female goddess and whose number is five. She’s somebody that people who have often been victimized by gender-based violence turn to for healing and sweetening.”

I was fascinated by this concept of active, playful, tangible relationships with multiple gods that require you to show up for them in your daily life. Inside this book, which is about a journey back and also through, I heard a testimony for getting lost, for losing yourself. I thought of the California I know and love. The dusty hot mountains to climb. The Joshua trees. The poppies along the cliff side leading into the ocean. We are lost, catharsis not more than a fantasy, and in its place, Gurba offers a hypnotic return to what we know, what we are, to land, to ourselves.