This post was originally published on this site

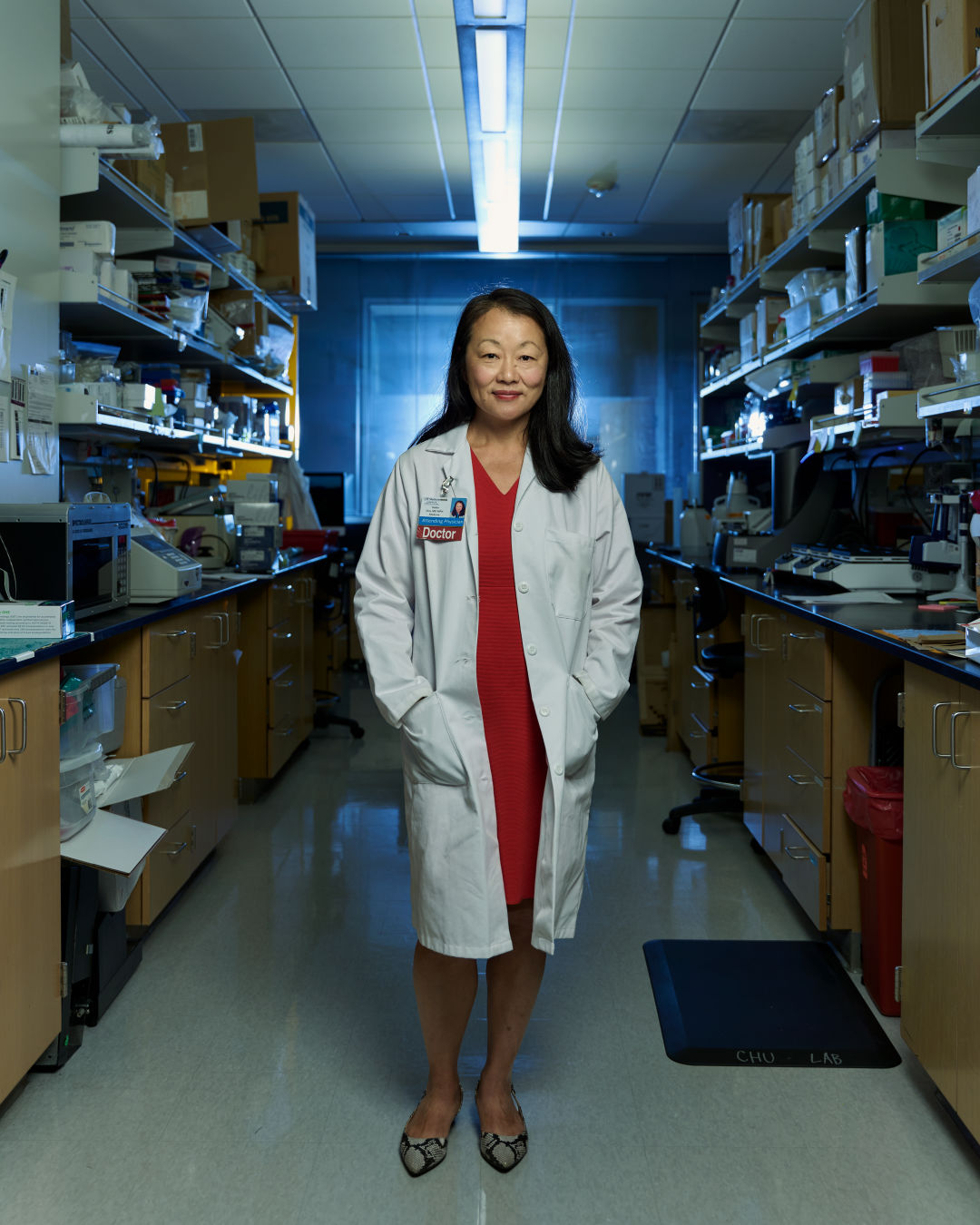

It took two years of vetting before Helen Chu was approved for her position on the CDC’s vaccine panel.

Dr. Helen Chu learned she had been fired in a Wall Street Journal op-ed. The UW Medicine physician and professor had been serving on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), helping guide vaccine policy in the United States when Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. announced a “clean sweep” of the advisory group.

Chu was on high alert after Kennedy’s appointment, knowing his skeptical stance on vaccines would paint a target on the 17-person group. But it was still a shock. “I did not expect that to happen, and certainly not in that manner,” Chu says.

A few hours after she read the piece, the termination emails arrived. And just two days later, a handful of new members had been announced to replace Chu and her ousted colleagues, who had spent years in approval processes.

Composed of family medicine practitioners and experts in immunology, vaccinology, and special populations like pregnant or immunocompromised patients, the ACIP interprets new data on vaccines to provide research-backed recommendations to the CDC. The independent panel’s recommendations inform CDC vaccine schedules: color-coded age charts with corresponding immunizations for all Americans.

In turn, the vaccine schedule becomes the holy grail by which states choose which vaccines to purchase for their populations and which to require for school admission. Private insurance companies use the schedule to determine covered immunizations. Vaccines for Children (VFC), the program that provides vaccines to kids without private health insurance—about 50 percent of US children—covers only the ones on the list.

Changes to the schedule create far-reaching ripples from which even privately insured patients aren’t insulated. If a vaccine is dropped from the schedule, private insurance companies could still choose to cover it, but Washington’s Health Department may not bulk-purchase the vaccine, meaning there would be little to no supply within the state. Even if patients wanted to get a vaccine that had lost its recommended status—say, something like the measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine—there may not be any doses available. Plus, the 50 percent of children relying on VFC would not receive the vaccine, stifling herd immunity necessary to prevent outbreaks.

Chu fears that private health insurers will choose not to cover certain vaccines in the future.

“I think that’s maybe what people don’t understand. They think, ‘Oh, I have private insurance, I will be safe.’ That’s not true,” Chu says.

Chu joined the committee as a voting member in July 2024. That appointment came after a two-year, “very extensive process of vetting” including disclosure and divestment from potential conflicts of interest, the buzzword that became the red herring Kennedy pinned his ACIP firings upon. Among the committee, those conflicts of interest usually came in the form of previous funding from pharmaceutical companies to run clinical trials—trials that provided essential experience to do the complex job the ACIP requires of its committee members.

Asking someone to parse ever-evolving data to make population-wide recommendations without that experience, Chu says, is like asking someone to fly a plane without a pilot’s license.

What now? Regardless of what direction a new ACIP forges, much is still up to individual states, and “we do have good public health systems in Seattle and in King County and in Washington state,” Chu reassures. The bad news? We’ve already had outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases like whooping cough, and Chu estimates those instances will continue to rise if vaccine schedules are changed. “It’s going to be confusing for everyone.”

For her part, Chu hopes the confusion is temporary. The dramatic ending of her tenure on ACIP hasn’t deterred her from wanting to continue the mission.

“I would always be honored to serve on the ACIP,” she says. “And hope that there will be a time when I can do so again.”