This post was originally published on this site

Everywhere I look, I see Octavia Butler. For example, not too long ago, a prominent funeral home in my part of town, Columbia City, was almost completely destroyed by an arsonist who was caught in the act by a video camera that was monitoring traffic on the intersection of Rainier and Alaska. Footage shows that he threw some fiery thing into the building’s window, it exploded, and he fled the scene with an air that can only be described as gleeful. Was this arsonist also behind the fire at a Mount Baker construction site, which happened the same night, July 30? And what about the suspicious fire that occurred the following day on Beacon Hill? And there are more fires, all suspicious, all in South Seattle. Was it just him? Or are we witnessing something like the opioid epidemic? A new way to get high? The sight of fire is now the drug?

This line of thought is not accidental. It comes directly from Octavia Butler, who, in her post-apocalyptic Parable series published in the 1990s, combined the crack epidemic of the 1980s, the history of American racism (which cannot be separated from its form of capitalism), and the increasing evidence of climate catastrophe to imagine a new a demonic drug that becomes all the rage in our ever-warming times.

This is how the main character of Parable of the Sower, Lauren Olamina, describes the effects of the drug called Pyro: “Then there’s that fire drug with its dozen or so names: Blaze, fuego, flash, sunfire.… The most popular name is pyro—short for pyromania. It’s all the same drug, and it’s been around for a while… It makes watching the leaping, changing patterns of fire a better, more intense, longer-lasting high than sex.”

This drug makes sense in the world Sower describes, which is a lot like the one we are in and, at present, can find no exit from—an Earth whose biosphere has been overheated by an economic system that can only survive if it grows yearly by, at minimum, 2 percent. And so it is. In both Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents, climate catastrophe does not, despite the unprecedented melting of polar ice and the larger and larger wildfires, slow capital accumulation. It accelerates it. And Pyro is a symptom of this acceleration. Instead of uniting humanity to fight climate catastrophe, all that capitalism can offer is a pill that allows you to enjoy its destruction or our one and only world. This is deep stuff. And this is why Octavia Butler, more than any other late-20th-century (and early-21st-century) author, is truly prophetic. Even the key works of the father of cyberpunk, William Gibson, feel dated when compared to Butler’s Parable series, which, understandably, was never completed. And it is this incompleteness that inspired Sabela grimes’s and Meena Murugesan’s masterful Parable of KinOptics, which was performed at Velocity on Saturday, August 9, with three local dancers: Akoiya Harris, Nia-Amina Minor, and Jade Solomon.

Murugesan and grimes are based in Los Angeles, and have consulted Butler’s archives at the Huntington Library in Pasadena to produce a work that doesn’t worship the master of speculative fiction, but, instead, finds itself in its fog.

One has to see Butler’s Parable series as a kind of probability clould: it floats, it shimmers, it evolves with possibilities that sometimes collapse and crystallize into what we in her future recognize as real events. And, indeed, this is how Butler described her mode of science fiction in a short article published in Essence Magazine in 2000, “A Few Rules For Predicting the Future”: “[T]here’s no single answer that will solve all of our future problems. There’s no magic bullet. Instead there are thousands of answers—at least.”

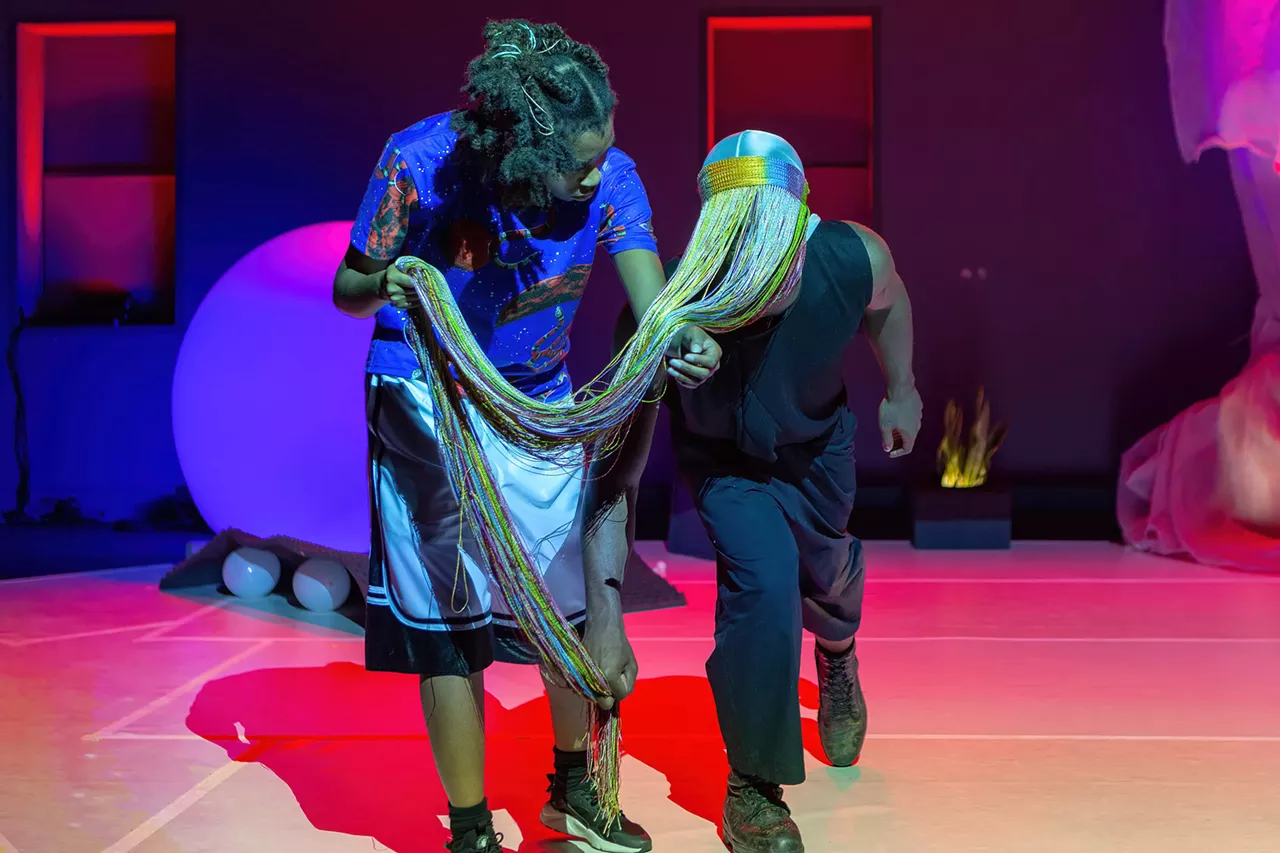

The Parable of KinOptics enters this cloud of potential with equipment that’s visual, textural, sartorial, musical, lyrical, and somatic. The images, which are often futuristic and otherworldly, are generated and projected by Murugensan. The movement through Butler’s spellbinding speculations and mass of archived notes is choreographed by grimes, who also produced much of the performance’s music and glittering wardrobe. He opens the show with an informal air. He doesn’t want to rush things. But eventually momentum begins to build as we approach the heart of what he calls “movement meditations,” which is three local dancers moving with the smoothness of Ariel-like beings through a future that flickers with images and words (often marginal notes) by Butler.

While watching KinOptics, I honestly became convinced that Butler is really the 21st century’s first philosopher. Baudrillard, who I think is underrated, pointed to the end of the 20th century; but it’s Butler who speaks for the one we are now in, the one that’s rapidly deteriorating within the current configuration of an economic space defined by the endless accumulation and concentration of value. The gorgeously bold Afrofuturist images on the screen, the transmissions of beats and lyrics, the soulful movements, the deep and yet playful meditations on time (grimes blends samples from rock, soul, and rap that mention time in different ways), the scintillating fog in which the whole work is formed and runs for about an hour, is powerful because this it is here “where [we] stay in reality” and nowhere else.

And yet The Parable of KinOptics is not a downer. It is instead empowering because its primary goal is to capture and assert something that’s central to Butler’s philosophy: the unusual intensity of our species-specific empathy. We are all, by nature, empathics like Sower’s narrator and founder of the post-apocalyptic religion Earthseed, Lauren Olamina. If anything, the struggle between us as we actually (meaning, socially) are, and the few powerful individuals who rule the dying world is the liberation or suppression of our ability to feel the suffering of others directly. Empathics are not freaks or from the future. They can only be who we are wherever we are. And this is the key to understanding a writer whose, to use the words of grimes, “pen game was off the chain.”